Navigating the Invisible: The Debate Over Personal Control of RFID Technology

Subtitle: As RFID chips become ubiquitous in cards, passports, and everyday items, discussions about privacy, security, and individual countermeasures intensify.

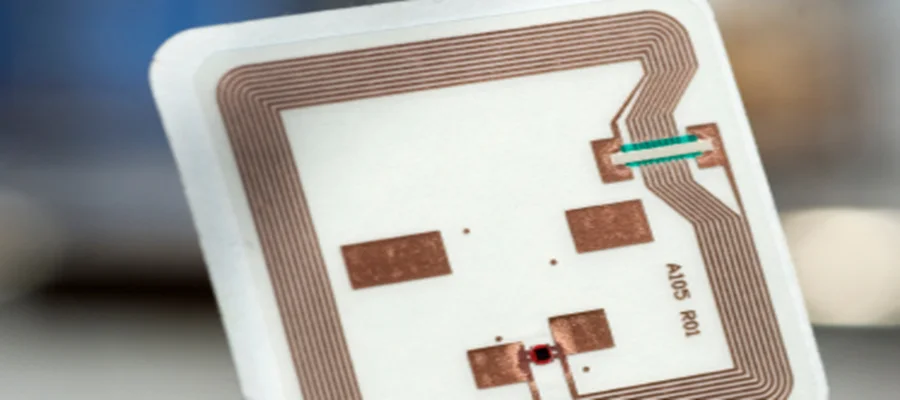

The tiny, unassuming Radio-Frequency Identification (RFID) chip is woven into the fabric of modern life. From enabling quick tap-and-pay transactions and providing secure access to buildings, to tracking inventory and embedding in passports, its utility is vast. However, its pervasive and often invisible presence has sparked a parallel conversation about personal privacy and the extent to which individuals can—or should—control these devices.

This debate often centers on the search for methods to block or deactivate RFID chips. The terminology used, such as "block & kill," underscores a desire for absolute personal control over digital interactions.

On one hand, the ability to block RFID signals is widely recognized as a legitimate privacy safeguard. This is typically achieved through Faraday cage principles. Products like shielded wallets, passport sleeves, and even DIY solutions using aluminum foil create a metallic barrier that prevents radio waves from reaching the chip, effectively making it invisible to scanners. This precaution is recommended by security experts to prevent "skimming," where unauthorized readers secretly harvest data from nearby chips.

The concept of killing a chip, however, ventures into more contentious territory. Permanently destroying an RFID chip, often by delivering a high-voltage electromagnetic pulse (EMP) through a powerful handheld device or by physically damaging it, is irreversible. While technically feasible, this action is often illegal, violates terms of service, and destroys the functionality of the item. Disabling a credit card chip voids its contract, "killing" a passport chip may invalidate the document, and tampering with retail security tags constitutes theft.

"The discourse isn't really about destruction," explains Dr. Elena Reed, a cybersecurity ethicist. "It's a symptom of a deeper anxiety. People feel their belongings—and by extension, their data—are no longer fully their own. The conversation about 'killing' chips is a visceral reaction to a perceived loss of autonomy."

Legitimate industries also employ "killing" mechanisms. Retailers deactivate RFID tags at checkout to prevent false alarms. Libraries disable tags in borrowed books. In these contexts, the deactivation is a controlled, authorized part of a transaction's conclusion.

The legal landscape is clear: while using a protective sleeve is your right, actively destroying chips embedded in property you do not fully own (like a company ID, a leased car key fob, or a government passport) can lead to serious legal consequences, including charges of vandalism or destruction of property.

As RFID technology continues to evolve, integrating into more personal devices and even medical implants, the dialogue is shifting. The focus is moving from radical individual countermeasures toward systemic solutions: stronger encryption standards, clear regulations on data collection, "right to know" laws about embedded chips, and the development of user-controlled chip protocols that can be switched on or off with permission.

Ultimately, the question posed by the search for ways to "block & kill" RFID is less about the technical how-to and more about a fundamental societal negotiation: In an increasingly networked world, where does corporate and governmental access end, and where does personal digital sovereignty begin? The answer will likely be found not in signal jammers, but in policy, transparent design, and empowered consumer choice.